Sexism & Heterosexism

by Anna Velychko

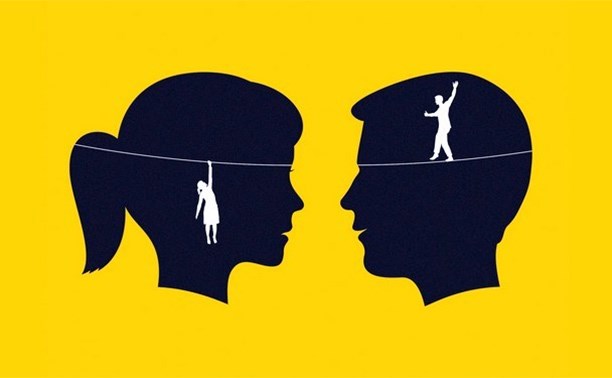

Women comprise half of the world’s population. Women’s achievements and contributions in the fields of business, science, or sports are often puzzling as if they are somewhat abnormal. Tavris (1992) claims that there is a widespread belief and conceptualizing of normalcy of men and the corresponding abnormality of women. Lenses of male-female dichotomy lead to widespread women’s discrimination in hiring, insurance, pensions or lending. Additionally, this perception imposes social norms and regulations about the normalcy of heterogeneous couples – any deviant from it (e.g., gay, bisexual, and transgender people) considers as divergent. The attitude to sexual discrimination from the point of law and positions of public practice varies: some forms of sexual discrimination are illegal, others – are fixed by law. In cases where the gender of a person is irrelevant, economic theories claim that sexual discrimination is ineffective and harmful to the economy. Although many types of gender discrimination in modern society have been officially abolished, women on average still get paid fewer than men, they are more likely to work part-time and occupy lower positions.

According to Levin (2000), sexism is an embodiment of “underlying patterns of gender inequality, discrimination, and – sometimes – hatred of women…” The author explains that gender, which is culturally and socially constructed, reinforces male supremacy and patriarchy in the society. In patriarchal societies, women and their qualities tend to be systematically judged against men. Because society imposes a certain set of rules and expectations (i.e., gender roles), it perpetuates the idea what “right” women should be like. Sexism includes lower pay scales for women than men, underrepresentation in many professions and overrepresentation in lower-paying occupations, sexual harassment and sexual objectification, and domestic violence (Miller, 2017). Gender inequality creates a ground for gender discrimination.

Gender discrimination is another significant aspect within inequality topic that cannot be ignored. In most societies, gender discrimination is seen as favoritism of men at the expense of women. Women are discriminated against in many areas of social life, that is, in the private and public spheres of social activity, such as employment, political and religious careers, housing, social policies, property rights in civil and criminal law. Discrimination by gender could be hidden or salient. Therefore, legislation designed to regulate discriminatory practices based on gender differences has a limited effect. Conversely, the ideology based on gender inequality serves to strengthen such practice, giving it legitimacy and making it a norm.

Policies that create complications for women to join the workforce maintain equitable salaries similar to men, as well as retain their employment (i.e., lack of paid maternity leave, lack of affordable child care, and others) contribute to the economic insecurity of women and their families (Stiglitz, 2015). Therefore, the author suggests rewriting and restructuring the rules to address gender equality, which will have higher moral and economic leverage. These rules would include rebalancing tax code, fixing the financial sector, incentivizing long-term business growth, making markets competitive, making full employment the goal, empowering workers, and expanding economic security and opportunity (Stiglitz, 2015).

Similarly to sexism, heterosexism is a way to favor certain groups of people over others. Unlike sexism that discriminates on the basis of gender, heterosexism described as “an ideological system that denies, denigrates, and stigmatized any nonheterosexual form of behavior, identity, relationship, or community” (Herek, 1990). It is a set of attitudes and beliefs that postulate a way of dating or family formation based on social ordering in society. Heterosexism intertwines with homophobia, which is expressed through an aversion to LGBTQI people. Miller (2017) states that sexual minorities become a target of oppression, which straight people do not face. People who identify as LGBTQI are subjects to discriminatory laws and policies, lesser protection under the law or the absence of thereof, historical and cultural erasure and others (Miller, 2017). Having to persevere and battle against heterosexual norms comes with great psychological costs. The LGBTQI population is less immune to depression, suicide, and drug use, and prone to develop “internalized homophobia” (Herek, 2000). As a society, we must recognize that we need to support and validate each other regardless of our gender identity or sexual orientation to foster a healthy and prosperous future for all.

Individual effects of homophobia will more likely manifest in lower rates of education, poor health, increased poverty, and, resultantly, weaker and reduced labor force (Westcott, 2014). As Ferro (2015) points out, discriminative policies, such as denying federal benefits to same-sex couples unlike heterosexual, put not only gay people in disadvantage but also devaluing human capital. It is not surprising that these excluding practices make people feel less deserving, less ambitious, and less motivated. I am grateful to have an opportunity to live in the United States. Even though there have never been openly transgender or gay senators or presidents in the United States, I still envision a promising future for same-sex couples and gay individuals in this country.

Being in the now, the reality differs from how it could potentially unfold in the future. In the light of proposed tax policy as of 2017, which slashes taxes for the wealthy and puts the rest in disadvantage, women face triple jeopardy (Abramovitz, 2013). According to Abramovitz (2013), there is a significant cut in public assistance, unpaid care work, and lack of assessing to public sector jobs for women. According to Abramovitz (1999), the lack of investigation and attention to poor women, immigrant women, and women of color in the social welfare literature portray essential aspects that need to be tackled upon to ensure the well-being and equal treatment for women. The author describes the concept of “family ethic” and how it plays a role in distinguishing between deserving and undeserving women. The family ethic imposes rigid gender roles, which make women economically dependent homemakers and assign them to caretaking roles (Abramovitz, 1999).

Locked in in the traditional gender role reinforces the idea like a self-fulfilling prophecy that women want or choose to stay at home. Otherwise, if employed, women are often overrepresented in lower-paying occupations. I think that there is an array of reasons to why exactly women get paid less. Here are some of them: 1. Throughout my research studies in Behavioral Economics and Industrial-Organizational Psychology (e.g., standardized testing, I came to realize that specific socially constructed gender differences begin during very early stages of human development, which are being perpetuated through the life course. Let’s consider clothing and toys. Girls are thought (or maybe just inclined) to wear pink clothes, play with dolls, and believe that they are not useful in sciences, sports, and other domains. These factors become internalized, which make girls think that they are less deserving, and, therefore, they become less competitive. This point ties to the following one. 2. Internalized values and beliefs in patriarchal society reinforce further discrimination in compensation, recruitment, and hiring. 3. The concept of “family ethic” imposes firm gender roles, which make women economically dependent homemakers and assign them to caretaking roles (Abramovitz, 1999).

The traditional and most common way to describe family emphasizes strong legal and procreation aspect. Some authors stress out the decline in reproduction as of our nation faces a catastrophe. According to Cha (2017), the birthrate is one of the most critical measures of demographic health, and that the birthrate as of 2017 fell one percent compared to a year ago. The author says, “If too low, there’s a danger that we wouldn’t be able to replace the aging workforce and have enough tax revenue to keep the economy stable.” However, there is not that much of emphasis in her or other research articles on how our government supports families with raising children. Having a child in the United States, especially in New York, is not cheap. I am not aware of any free daycare centers, valuable education institutions free of charge, as well as low-cost insurance coverage. Therefore, I argue that the wage gap needs to be addressed on the governmental level.

According to Abramovitz (2008), “Between 1970 and 2005 the proportion of married couples with two earners jumped to 62 percent from about 46 percent, Labor Department data show. The U. S. Women’s Bureau finds wives’ contribution to family income rose to 35 percent from 26 percent.” Joining a workforce is not necessarily a matter of choice for women, but more of a reflection to a family’s struggles to make ends meet in the face of stagnant wages and job loses. This is a widespread issue that results in an economic downturn. According to Aziz (2013), sex- and/or race-based discrimination is disproportionally correlated with economic productivity. There is a higher chance for the economy and productivity to thrive when discrimination decreases and work opportunities open up to all people according to their aptitude rather than race or gender. The author argues that barriers to professional jobs must be reduced to shed light on people who have the talent to perform well at the job (Aziz, 2013), they need to be given an opportunity and access to these jobs. Similarly to Aziz (2013), Jim Yong Kim (2014), president of the World Bank Group, stated, “Widespread discrimination is also bad for economies. There is clear evidence that when societies enact laws that prevent productive people from fully participating in the workforce, economies suffer.”

Establishing more equitable and fair society is a long gradual process, but it had started. By enhancing the autonomy and independence of women and LGBTQI people, there is a likelihood of promoting family development based on reliable, loving, and supportive bonds, in addition to financial security. In turn, economists and politicians must agree that enhancing people’s rights will not only ensure humane and respectful treatment for all but will also foster economic growth.

Annotated Bibliography

Abramovitz, M. (1999). Regulating the lives of women. Social welfare policy from colonial times to the present (Revised edition). Boston, MA: South End Press.

Abramovitz, M. (2013). Triple Jeopardy: Dismantling the Public Sector and the War on Women, Retrieved from http://www.roosevelthouse.hunter.cuny.edu/?forum-post=roosevelt-house-faculty-op-ed-triple-jeopardy-dismantling-public-sector-war-women

Abramovitz, M. (2008). Wall street takes welfare it begrudges to women. We News. Retrieved from http://womensenews.org/2008/09/wall-street-takes-welfare-it-begrudges-women/

Aziz, J. (2013). Less racism-sexism means more economic growth. The Week. Retrieved from

http://theweek.com/articles/454335/less-racism-sexism-means-more-economic-growth

Cha, A.E. (2017). The U.S. fertility rate just hit a historic low. Why some demographers are freaking out. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/to-your-health/wp/2017/06/30/the-u-s-fertility-rate-just-hit-a-historic-low-why-some-demographers-are-freaking-out/?utm_term=.0b7141c8851c

Ferro, J. (2015). Homophobia is bad for the economy. Business Insider. Retrieved from http://www.businessinsider.com/ubs-homophobia-is-bad-for-the-economy-2015-7

Herek, G.M. (2000). Internalized homophobia among men, lesbians, and bisexuals, in M. Adams, W.J. Blumenfeld, R. Castaneda, H. W. Hackman, M.L. Peters, & X. Zuniga (Eds.), Readings for diversity and social justice (pp. 281-283). New York, NY: Routledge.

Herek, G. M. (1990). The context of anti-gay violence: Notes on cultural and psychological heterosexism. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, Vol. 5, (pp. 316-333).

Kim, Y.J. (2014). Jim Yong Kim: The high costs of institutional discrimination. The World Bank. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/jim-yong-kim-the-high-costs-of-institutional-discrimination/2014/

Levin, J. (2000). Gender Inequality, in Chapter 4 of Social Problems: Causes, Consequences, Interventions, 2nd Ed. (pp. 82-104). Los Angeles: Roxbury.

Miller, J. & Garran, A.M. (2017). Intersectionality: racism and another forms of social oppression. In Chapter 7 of Racism in the United States 2nd Ed. (pp. 171 – 203). New York, NY: Springer Publishing.

Stiglitz, J. (2015). Rewriting the rules of the American economy. Roosevelt Institute. Executive Summary and Introduction, (pp. 7-22). Retrieved from http://rooseveltinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Rewriting-the-Rules-Report-Final-Single-Pages.pdf

Tavris, C. (1992). The Mismeasure of Women. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Westcott, L. (2014). What homophobia costs a country’s economy. The Atlantic. Retrieved from: https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2014/03/what-homophobia-costs-countrys-economy/359109/

Welsch, J. G. (2008). Playing within and beyond the story: Encouraging book-related play. The Reading Teacher, 62 (2).